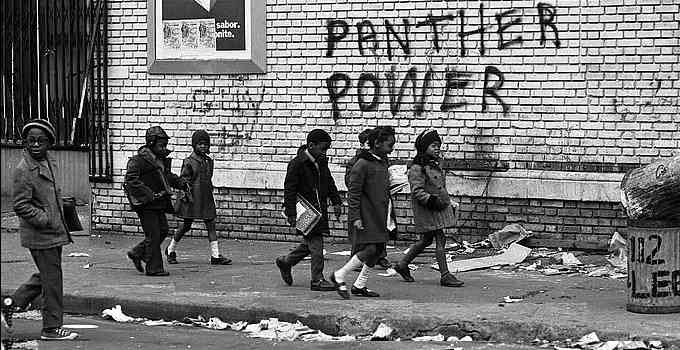

b(l)ack panthers

all power to the people

Bella Italia

Italy is a highly evolved feudal society

In Italy, Questions Are From Enemies, and Thats That

ROME I got a call last week from an Italian friend, an investigative reporter. He had just spoken to an Italian magistrate who wanted to sound out a theory.

The magistrate wondered in all seriousness if my recent article in The New York Times about Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconis personal life could be evidence that Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, envious of Mr. Berlusconis media empire, was using me to take down the prime minister.

My friend quickly and rightly dismissed the theory for what it was: insane. But the fact that it had been advanced by a respectable magistrate tells you almost everything you need to know about how power operates in Italy. It also goes a long way toward explaining the unstoppable success of Mr. Berlusconi, a phenomenon as alien to Americans as conflict-of-interest laws are to Italians.

Americans are forever asking how Italy can keep voting for Mr. Berlusconi, whose legal problems not to mention his wifes recent threats of divorce and accusations about her husbands dalliances with very young women would have toppled governments elsewhere.

But Italians dont always see things this way. In Italy, abuse of office is something of a foreign concept, even though an Italian court is now investigating whether Mr. Berlusconi committed it when he used government planes to shuttle guests, including a Neapolitan singer and a flamenco dancer, to gala parties at his villa in Sardinia.

Mr. Berlusconi has brushed this off, as he has all other claims of impropriety, as a campaign against him by left-wing magistrates and journalists. He says they want to discredit his center-right coalition ahead of this weekends elections for the European Parliament, which he is still expected to win.

While wildly off target in my case, the magistrates Bloomberg theory is not entirely crazy. Mr. Berlusconi last week suggested in an interview that The Times of London had published critical editorials about him because it is owned by Rupert Murdoch, whose Sky is the largest player in the Italian cable television market after Mr. Berlusconi.

In Italy, this is seen as business as usual. The general understanding is that everyone uses the means at his disposal to fight his rivals.

The real issue here is that Italy is not a meritocracy. It is a highly evolved feudal society in which everyone is seen as and inevitably is the product of a system, or a patron.

During the postwar years, the American-backed Christian Democrats, Moscow-backed Communists and business-minded Socialists had their own networks of politicians, bankers, lawyers and their own press organs. That corrupt patronage system collapsed with the end of the cold war and a huge bribery scandal.

Today, there is no ideology and no network; there is only Mr. Berlusconi, and you are either with him or against him. Compared to the old order, Mr. Berlusconis political class is seen as a modernizing force. Mr. Berlusconis rivals accuse him of being on the wrong side of the law, and he in turn accuses them of being on the wrong side of history. Those two things shouldnt cancel each other out, but often do.

The members of the Italian left have been infighting since the collapse of the Berlin Wall and are so weak and ineffective today that some in this land of byzantine conspiracy theories believe that Mr. Berlusconi must be paying them off.

Italy is deeply confusing for Americans, who are steeped in notions of speaking truth to power and following the money, raised in the country of Yes we can, not Sorry, Signora, thats impossible.

In the topsy-turvy logic of Italy, Mr. Berlusconis unrivalled grip on the public and private sectors and media outlets doesnt make him seem compromised. Instead, his supporters see him as rich enough to be independent. As one working-class Roman told me not long ago, full of admiration, hes so rich, he didnt even need to go into politics.

In Italy, when journalists ask completely legitimate questions about the legal status and personal life of the leader of a Group of Eight country or even when they ask why Italy doesnt seem to care about the answers they are inevitably accused of insulting the prime minister or of being the pawns of larger interests.

In Italy, the general assumption is that someone is guilty until proven innocent. Trials in the press and in the courts are more often about defending personal honor than establishing facts, which are easily manipulated.

Sometimes I wonder what Pope Benedict XVI, who has railed against the dictatorship of relativism, in which equating all beliefs leads to nihilism, would make of Italy. Here, information is used less to clarify than to obfuscate.

How else to interpret the barrage of wildly contradictory material that has emerged in the press in recent weeks about how Mr. Berlusconi met Noemi Letizia, whose 18th birthday party he attended in April an act that so angered his long-estranged wife that in threatening divorce she became de facto opposition leader?

In the absence of a clear, coherent story, the only standard of evidence becomes personal loyalty.

Ms. Letizia said in an interview last week that she was upset that her new boyfriend had auditioned for the reality television show Big Brother without asking her permission.

In the reality show that is todays Italy, Mr. Berlusconi is the clear winner. His rivals are doing little more than throwing tomatoes on stage. The actor is showing signs of fatigue, but the audience is glued to its seats. Après lui, le déluge.

Source-Quelle-Fonte: New York Times - June 7, 2009

L'Italia e una società feudale molto evoluta

In Italia le domande le fanno i nemici, punto<

Roma - Ho ricevuto una telefonata la scorsa settimana da un amico italiano, un reporter investigativo. Aveva appena parlato con un magistrato italiano che voleva sondare una teoria. Il magistrato si chiedeva - in tutta serietà - se il mio recente articolo sul New York Times sulla vita personale del Presidente del Consiglio Silvio Berlusconi potesse essere una prova che il sindaco Michael R. Bloomberg, invidioso dellimpero mediatico di Berlusconi, mi stesse usando per smontare il Presidente del Consiglio.

Il mio amico ha rapidamente e giustamente scartato la teoria per quello che era: insensata. Ma il fatto che fosse stata avanzata da un rispettabile magistrato vi dice quasi tutto quello che avete bisogno di sapere su come funziona il potere in Italia. La dice lunga anche sul successo inarrestabile di Berlusconi, un fenomeno tanto strano per gli americani quanto lo sono le leggi sul conflitto di interessi per gli italiani.

Gli americani si chiedono da sempre come lItalia possa continuare a votare Berlusconi, i cui problemi legali -per non menzionare le recenti minacce di divorzio da parte della moglie e le sue accuse di flirt del marito con donne molto giovani- avrebbero rovesciato i governi da qualsiasi altra parte.

Ma gli italiani non sempre vedono le cose in questo modo. In Italia, labuso dufficio è una sorta di concetto astratto, nonostante un tribunale italiano stia ora investigando se Berlusconi labbia commesso quando ha utilizzato aerei del governo per trasportare ospiti, inclusi un cantante napoletano e una ballerina di flamenco, a feste di gala nella sua villa in Sardegna.

Berlusconi ha liquidato tutto ciò, come ha fatto con tutte le altre accuse di scorrettezze, come una campagna contro di lui organizzata da magistrati e giornalisti di sinistra. A suo avviso, vogliono screditare la sua coalizione di centro-destra in vista delle elezioni di questo weekend per il Parlamento Europeo, che ancora una volta si aspetta di vincere.

Sebbene largamente fuori dallobiettivo nel mio caso, la teoria del magistrato su Bloomberg non è del tutto insensata. Berlusconi la scorsa settimana ha ipotizzato in unintervista che il Times di Londra avesse pubblicato editoriali critici su di lui perché di proprietà di Rupert Murdoch, proprietario di Sky ovvero il più grande attore nel mercato della TV italiana via cavo dopo Berlusconi.

In Italia, questa è ordinaria amministrazione. Lopinione generale è che tutti usano i mezzi a propria disposizione per combattere i propri rivali.

La vera questione qui è che lItalia non è una meritocrazia. E una società feudale molto evoluta in cui ognuno è visto, ed inevitabilmente è, il prodotto di un sistema, o di un protettore. Durante gli anni del dopoguerra, i democristiani appoggiati dagli americani, i comunisti appoggiati da Mosca e i socialisti orientati al mondo del business avevano le proprie reti di politici, banchieri, avvocati, e i propri organi di stampa. Quel sistema di patrocinio corrotto è crollato con la fine della guerra fredda e con un enorme scandalo di tangenti.

Oggi non ci sono né ideologie né reti; cè solo Berlusconi, e si può essere con lui o contro di lui. In confronto al vecchio ordine, la classe politica di Berlusconi è vista come una forza modernizzatrice. I rivali di Berlusconi lo accusano di essere sul lato sbagliato della legge e lui a sua volta accusa loro di essere sul lato sbagliato della storia. Queste due cose non dovrebbero escludersi a vicenda, ma spesso lo fanno. I membri della sinistra italiana sono stati in lotta interna sin dal crollo del Muro di Berlino e sono così deboli e inefficaci oggi che alcuni in questa terra di teorie intricate di cospirazione sono convinti che Berlusconi li stia pagando.

LItalia è profondamente confusa per gli americani, che sono immersi in concetti quali dire la verità per governare e inseguire il denaro, cresciuti nella terra del Si possiamo, non del Mi dispiace, signora, questo è impossibile. Nella logica capovolta dellItalia, il controllo senza rivali di Berlusconi sui settori pubblico e privato e sui media non lo fanno apparire compromesso. Al contrario, i suoi seguaci lo vedono abbastanza ricco da poter essere indipendente. Come mi ha detto un romano della classe operaia non molto tempo fa, pieno di ammirazione, è così ricco che non aveva nemmeno bisogno di mettersi a fare politica.

In Italia, quando i giornalisti fanno domande del tutto legittime sullo stato legale e la vita personale del leader di un paese del G8, o persino quando chiedono perché lItalia non sembra importarsene delle risposte, sono inevitabilmente accusati di insultare Presidente del Consiglio o di essere le pedine di interessi più grandi.

In Italia, il presupposto generale è che qualcuno è colpevole finché non provato innocente. I processi, nella stampa e nei tribunali, riguardano più spesso la difesa dellonore personale che stabilire i fatti, che sono facilmente manipolati. A volte mi chiedo cosa ne pensa dellItalia Papa Benedetto XVI, che ha inveito contro la dittatura del relativismo secondo la quale equiparare tutte le credenze porta al nichilismo. In Italia linformazione è usata non per chiarire, ma per annebbiare.

Come altro interpretare la raffica di materiale largamente contraddittorio emerso dalla stampa nelle settimane recenti, su come Berlusconi abbia incontrato Noemi Letizia, alla cui festa di 18esimo compleanno il Premier ha partecipato ad Aprile, un atto che ha fatto talmente infuriare sua moglie, da molto lontana dai riflettori, che con la sua minaccia di divorzio è ora diventata il leader di opposizione de facto? In assenza di una storia chiara e coerente, lunico standard di prova diventa la lealtà personale.

Noemi Letizia la scorsa settiamana ha dichiarato in unintervista di essere arrabbiata perché il suo nuovo fidanzato aveva fatto un provino per il reality televisivo Grande Fratello senza chiederle il permesso. Nel reality che è lItalia di oggi, Berlusconi è il palese vincitore. I suoi rivali stanno facendo poco più che lanciare pomodori sul palco. Lattore sta mostrando segni di stanchezzza ma il pubblico è incollato ai propri posti. Dopo di lui, il diluvio [in francese nel testo, N.d.T.].

Source-Quelle-Fonte: Italia dall'estero - New York Times - June 7, 2009

Could a teenage girl topple Berlusconi?

She calls him 'daddy'. He bought her a £6,000 necklace for her 18th. Silvio Berlusconi's relationship with Noemi Letizia has already seen his wife file for divorce. Now, could it cost him his grip on power?

By Peter Popham

Italians are always scornful about the obsession of the "Anglo-Saxon" media with the private lives of the rich and famous, but for the past month the Italian newspapers have been preoccupied with one subject and one subject only: the relationship between Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and a young woman from Naples called Noemi Letizia.

Mr Berlusconi has been caught out telling numerous lies about the relationship and refuses to explain them. And with important elections pending, his popularity, at an all-time high only six weeks ago, may be eroding.

The media cannot be accused of muck-raking on the issue because it was Mr Berlusconi himself who drew attention to the relationship in Tuesday when he took advantage of a trip to Naples to drop in on Noemi's 18th birthday party. There he posed for photographs and presented the pretty young blonde with a gold and diamond pendant worth 6,500 (£5,700). This unremarkable event was immortalised in a short news story the next day in La Repubblica.

And there it would have ended, except that within four days it provided Mr Berlusconi's second wife, Veronica, with the casus belli for a divorce. Her husband, she said in a press release, was "consorting with minors"; he was "not well", she was worried about him, but in the meantime, after nearly 30 years together, she was in no doubt that the marriage was over.

Suddenly that innocuous-seeming social event assumed mysterious and sinister overtones. Noemi, it was learned, called Mr Berlusconi "papi", Italian for "daddy". He seemed on remarkably familiar terms with the girl. Pushed into a corner by Veronica, who opens her mouth about once every two years but with devastating effect, Berlusconi went on Porta-a-Porta, a late-night political chat show hosted by his most unctuous TV courtier and explained that Noemi's father Elio Letizia was an old political contact from his days when he was connected to Bettino Craxi and the Socialist party: Berlusconi needed to see him on urgent European election business. But soon afterwards Bobo Craxi, son of the late Bettino, popped up and said he had never heard of Noemi's father. Likewise Mr Berlusconi's unlikely claim about "election business" failed to pan out, and some weeks later was denied by Letizia himself.

The personal was personal no more: something about that birthday party, and Mr Berlusconi's presence at it, had tipped the long-suffering Veronica over the edge. One reason for her anger, as she explained in a bitter email to the Ansa news agency, was the fact that he had failed to turn up to the coming-of-age parties of any of the their own children, "even though he was invited". But that in itself could not be la goccia che ha fatto traboccare il vaso, (or as we would say, the straw that broke the camel's back). Could Berlusconi be the lover of Noemi, and thus perhaps guilty as Veronica suggested of "consorting with minors"? Or might she be his love child? Her plump cheeks and currant eyes, not that dissimilar to the Prime Minister's, allowed the world to guess at the latter possibility. But Mr Berlusconi flatly refused to shed any light on their relationship. He insisted that he had only met her "three or four times", and always in the company of her parents.

The irony is that never before has Berlusconi showed any coyness about exposing his colourful and chaotic private life to the public gaze. He fell in love with Veronica when she appeared topless in a play called The Magnificent Cuckold in Milan, and lived in sin with her for 10 years before marrying her in a civil ceremony; their children were born before the wedding. When he went into politics in 1994 his manifesto was a bowdlerised autobiography, Una Storia Italiana, depicting himself as the Italian everyman, the bank manager's son from nowhere who had grown immensely rich through hard work, a home-loving family man in touch with his common roots. Italians in their millions swallowed it, yet no-one doubted (you just had to look at his two wives) that he had an eye for the girls.

It was after his second and much more convincing election victory in 2001 that the rumours about Berlusconi's frenetic affairs began to circulate in earnest, with talk of a beautiful young intern being taken to his Sardinian villa for the summer as his "assistant" and the rapid promotion of others who were similarly eye-catching through the ranks of his party, Forza Italia, by way of his commercial television channels. Berlusconi the ageing roué had found the perfect way to keep his libido engaged, despite the demands of politics. And this being Italy, nobody made a fuss. Veronica had been settled in a magnificent house a few kilometres from Berlusconi's main home, Villa Arcore, north of Milan. He was obviously a bad husband, but in Italy that was nobody's business but the family's.

Yet as the editor of La Repubblica, Ezio Mauro, pointed out yesterday: "Mr Berlusconi long ago destroyed the boundaries between the public and the private." He did it when he published his manifesto. And he continued to do it in a more chaotic, impulsive way when he allowed the paparazzi to snap him hanging out with busty showgirls 50 years his junior. It was the behaviour of a sultan, a monarch or a dictator, and the way Berlusconi was pushing the envelope was an indication of how he was steadily moving in that direction. His own newspapers and television channels would never cry foul. RAI, the national broadcaster, was increasingly under his thumb. Even the independent dailies were more and more reliant on his goodwill. Berlusconi's growing recklessness about his image became a barometer of his increasing sense of personal invulnerability.

But he was reckoning without Veronica. It was in January 2007 that she first told the world that he had gone too far, granting an interview to La Repubblica (one of the few really independent dailies), in which she demanded that he apologise for saying of Mara Carfagna, a glamour model turned MP (and now a cabinet minister), "I would marry her like a shot if I wasn't married already." Meekly Berlusconi consented. But he didn't reform. He carried on just as before, until Noemi's 18th birthday rolled around and it all went horribly wrong.

Today Italy is at an impasse: La Repubblica has insistently demanded that Berlusconi come clean about Noemi, for the last two weeks publishing a list of 10 questions it wants him to answer. Berlusconi has repeatedly refused. With European elections just 10 days away, there is a real risk that his silence will injure him in polls he was expected to win with ease particularly now that respected figures in the Catholic church like the former Archbishop of Pisa Alessandor Plotti have begun to attack him. Berlusconi has said he may make a statement to parliament in response to what he calls the "vile reports" about his relationship with Noemi.

It is symptomatic of the trivialisation of Italian politics under Berlusconi that he is now being held to account, not for corruption, or mafia connections, but because of his relationship with a teenage girl. But the fight itself is not trivial. Living in Italy now is like being trapped in a field of lava slowly but irreversibly sliding down a mountainside. Far from leading to a revitalised "Second Republic", Italy's bribery scandals of the 1990s instead ushered in the Age of Silvio and the slow, steady degradation of the nation's democratic institutions. If the Prime Minister can get away with carrying on an adulterous, semi-public love affair with a teenage girl (and then lying so brazenly about it that any fool can see he is not telling the truth) and still he is not brought to account then the nation is in danger.

Quelle-Fonte: The Independent

look at the added logo on italian public television